= ASTRONAUTICAL EVOLUTION =

Issue 113, 1 May 2015 – 46th Apollo Anniversary Year

26th Mariner Anniversary Annum

| Site home | Chronological index | About AE |

Mars: Still So Distant, 25 Years After Mars Direct

A planet critical for future human growth

Ever since Von Braun published Das Marsprojekt, the Red Planet has loomed large in the astronautical imagination as the “ultimate goal”: tantalisingly Earthlike, maybe with its own indigenous life, certainly the most exciting target for exploration, definitely the most likely location for the first permanent extraterrestrial settlement, and possibly with the ultimate potential to be terraformed into a new Earth.

I believe it’s correct to regard Mars as very much a test case for what humanity is capable of. Mars possesses the material resources on which a new branch of civilisation could be built, in combination with the closest analogue to a terrestrial surface landscape found anywhere in the Solar System.

Venus with its closely Earthlike gravity is interesting, but demands a new mode of life aboard floating sky-cities. Compared with Mars, Venus requires a greater investment of start-up infrastructure, since its rocks and metals are relatively inaccessible at the bottom of a global ocean of superheated carbon dioxide. Orbiting space colonies constructed from asteroidal materials will surely come, but again make greater technological demands when those rocks must be processed in a microgravity vacuum to produce infrastructure of sufficiently high quality to bear the tensile stresses of internal pressure and rotation. The Moon is easiest of access, but combines a low-gravity, dusty vacuum surface environment with a shortage of volatiles over most of its surface.

On Mars, by contrast, rocks and ice, some basic gravity, atmospheric gas and a working flat surface to stand on and build on are available over the entire planet.

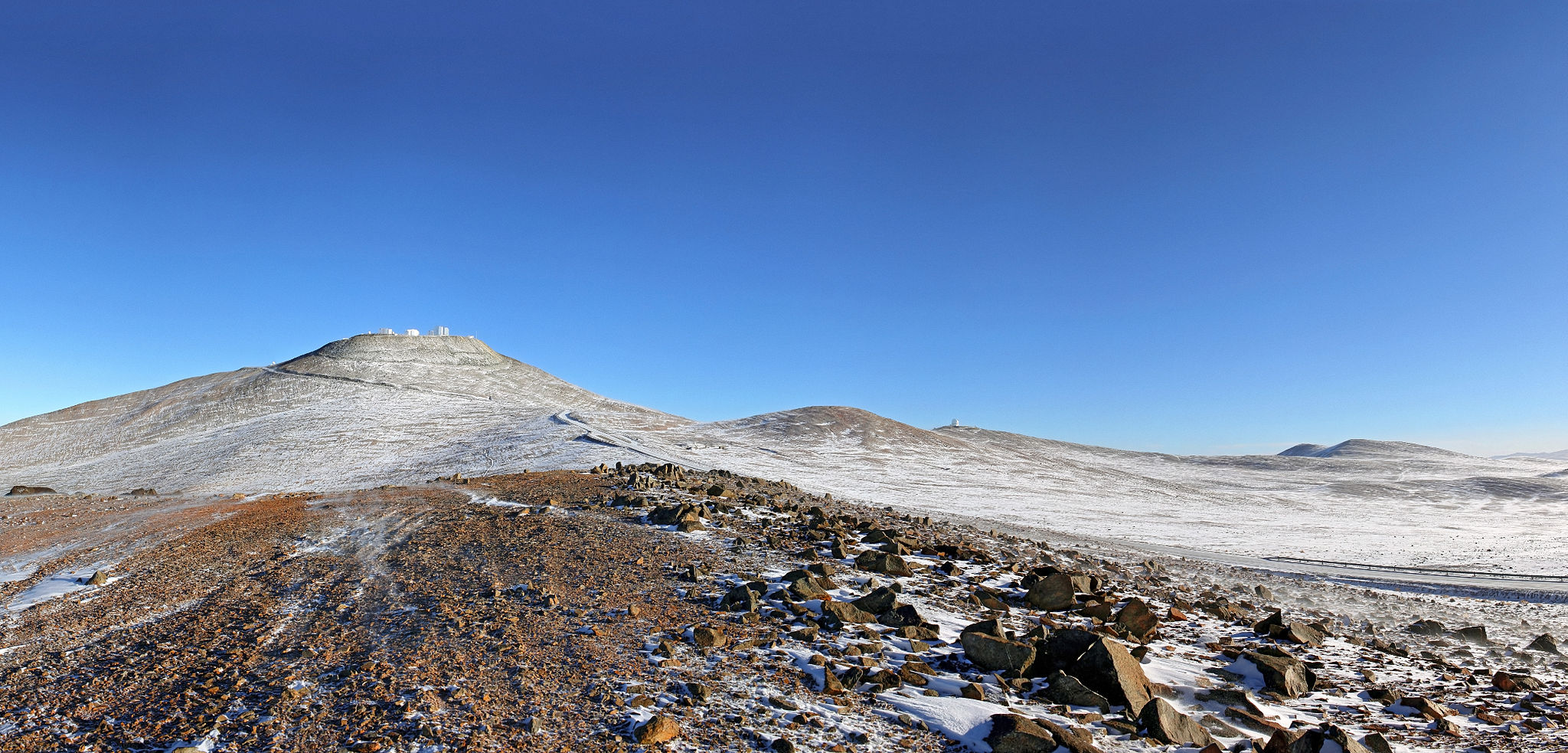

It would seem to be a small step from a cold high-altitude desert on Earth to the surface of Mars. Although the length of the journey there and back would be about 100 times greater than the Apollo Moon flights, the Apollo flights were themselves 100 times longer than Yuri Gagarin’s first orbital flight less than ten years earlier. The velocity cost of getting to Mars and back is not much greater than it is for the Moon, and refuelling at the destination is possible. Technology has moved on since the 1960s. Surely we are now ready to tackle Mars?

This is the low-hanging fruit of the Solar System. If we cannot make it on Mars, then we’re not likely to be able to settle anywhere else beyond Earth, either in our own Solar System, or beyond.

But reaching Mars with manned spacecraft is still a difficult nut to crack, and settlement of Mars even more so.

A planet tantalisingly out of reach

Settlement of Mars, rather than a token Apollo-style visitation, represents four problems rolled up into one.

(1) Transport: nobody has yet flown to Mars. The nearest analogue we have is the Apollo-Saturn system for getting to the Moon. This cost on the order of $100 million per person, and was designed for winning a race, not the kind of regular access that permanent settlement requires. In terms of journey time, access to the Moon is two orders of magnitude faster than access to Mars, and whereas the Moon is accessible from Earth all year round, Earth–Mars trajectories open up for only a short period which occurs only once every couple of years. Despite the Moon’s relative accessibility, no manned flights have taken place since the last Apollo visit in December 1972.

(2) Life-support: nobody has yet demonstrated a fully sustainable system for living independently of Earth’s biosphere. The best attempt so far was the Biosphere 2 project in the early 1990s. The facility cost on the order of $30 million per person, despite being located right here on Earth. One of the biospherians, Jane Poynter, later wrote: “After 13 months in Biosphere 2, we were starving, suffocating, and going quite mad” (The Human Experiment, p.245). Nothing on that scale (8 people enclosed for 2 years) has yet been attempted since.

(3) Acclimatisation: the one feature of Mars which human immigrants cannot avoid is the local gravity, at only 0.38 of one Earth gee. Nobody yet knows how the human body will respond. What we do know is that humans adapt badly to microgravity, so given present knowledge long-term living in microgravity is not desirable and not possible. Whether living in 0.38 gee will be 38% better than microgravity, or more than 38%, or less, is unknown.

(4) Sustainable growth: if a planet is to be settled, then life there must be attractive, sustainable and capable of growth, from an initial base of a handful of people to a town of thousands and then cities of millions. Obviously this has been done many times on Earth, but not yet at any extraterrestrial location.

Think what this means. Cockell highlighted the environmental harshness of Mars compared with even the remotest terrestrial desert. In a nutshell, it will never be possible to go outside to take a breath of fresh air, even on the sunniest of days. The consequence is that people will be permanently restricted to their accommodation buildings, vehicles and spacesuits. This will be similar to living in Antarctica, with the difference that all these protective enclosures must be hermetically sealed and pressurised with breathing gas. Cockell’s point is that Earth’s Arctic and Antarctic remain places to visit, not to live permanently, and the same must therefore apply, with even more force, to Mars.

And while we’re looking for problems, we also need to recognise the strand of opinion which would condemn any manned landing on Mars as “contamination” of the planet or as otherwise scientifically or ethically unacceptable – as argued for example by Robert Walker.

Ambitious plans for colonising Mars

Despite the difficulties, private organisations exist today dedicated to the goal of colonising Mars, of which the most prominent are the US-based Mars Society and Mars Foundation (not to be confused with the Inspiration Mars Foundation, whose goal is currently limited to launching a Mars flyby in 2018), and the Dutch-based Mars One.

While there is no doubt some crossover, the Mars Society is based historically on Robert Zubrin’s Mars Direct plan, which would be a NASA programme. In contrast, the controversial Mars One project, founded by Bas Lansdorp and Arno Wielders, is devoted to a commercially funded private programme, not a government one.

The Mars Foundation, founded and directed by Bruce Mackenzie, a former executive director of the Mars Society, has announced an ambitious Mars Homestead Project whose mission is “to design, fund, build and operate the first permanent settlement on Mars”. Prototype projects are to “lead the Mars Foundation to the establishment of an entire simulated Mars settlement at a location here on Earth” – presumably going further than the Mars Society’s existing small-scale experiments on Devon Island and in Utah. The emphasis on related NASA programmes on their website leaves no doubt that the Mars Foundation, like the Mars Society and despite their bold ambition to fund the first settlement, envisages NASA leading the way to Mars.

For completeness, we should add that NASA itself is also running a Mars simulation in Hawaii, and ESA has carried out a similar experiment in Moscow.

While the Mars Foundation’s main focus is on how to survive on Mars after arrival, the other two groups both have a strong focus on Earth–Mars transport. Zubrin has emphasised the point that the first landing should take place within a decade of programme start; Mars One is currently aiming for a first landing mission launched in 2026. Zubrin’s strategy would be in a race against political apathy and bureaucratic sclerosis; Lansdorp would be committed to a tight schedule if his supposed funding is to keep flowing.

What are we to think of these projects? Mars One has attracted a great deal of criticism – see for example this post by planetary scientist Laura Seward Forczyk. It must be clear that at the current costs of space exploration, manned flights to Mars are well beyond any privately funded programme.

Later in 2015, it is reported, the CEO of SpaceX, Elon Musk, will be announcing more details of his own plans for Mars colonisation. Might he have a better chance of success? On the one hand, it’s surely rash of him to talk about colonising Mars when SpaceX has not yet demonstrated solutions to any of the specific problems listed above, and has not yet even flown a single astronaut. On the other hand, for the first time ever such plans are being drawn up by a company which is regularly flying its own vehicles for commercial customers and for supply of the International Space Station, and is under contract to begin flying astronauts within a couple of years. Perhaps we should suspend judgement until more is known of what Musk and SpaceX intend to do.

Robert Zubrin first presented his Mars Direct plan to the public at a conference of the National Space Society on 28 May 1990 (The Case for Mars, p.65). Mars Direct has therefore spent a full quarter of a century in the public domain. During that time, despite much enthusiasm within the space community and a supportive NASA administrator, neither NASA nor any other government space agency has committed itself to the plan, or to anything similar. Whatever space administrators may think, they are dependent upon political will to turn such visionary plans into public policy funded by government, and no government anywhere in the world has yet shown any more than token interest in exploring or colonising Mars.

In his book, Zubrin gives the impression of a smooth transition from initial exploration missions, firstly to a permanent Mars base, ultimately to large-scale colonisation. I have always found this hard to swallow. Why? Because I am an “orphan of Apollo” – someone who expected Apollo to lead on to permanent Moon bases, and was let down by that programme’s cancellation.

What if Mars Direct were to become official US government policy after the next presidential election, and Robert Zubrin appointed NASA Administrator with powers to push the programme through exactly as described in his book? The result, in my view, is certain: the programme would be cancelled! If we were lucky, it would be like Apollo and be cancelled after achieving a few landings. Been there, done that!

If unlucky, it would be like the X-33 VentureStar, cancelled after $1.5 billion had been spent, but before any hardware had flown, or ESA’s Hermes spaceplane, again cancelled after $2 billion had been spent. Or, indeed, like NASA’s own Constellation programme, which was first cancelled, then resurrected in the form of the current Orion/SLS architecture, but in both cases saddled with the kind of risk-aversion and high costs which make a sustained flight programme impossible.

The same applies all the more to various space agency based Mars plans which offer alternatives to Zubrin’s Mars Direct architecture, such as the recent proposal publicised by The Planetary Society for a manned Mars orbital mission to be launched in 2033 – of which Zubrin said: “This is not a plan to send humans to Mars. This is a plan to pretend to be thinking about sending humans to Mars.”

I conclude that at the present time, neither governments nor private ventures are able to send astronauts to Mars in any sustainable fashion.

This is the problem which anyone who wishes to see our species expand from one planet to become a spacefaring civilisation must face up to.

Both NASA and The Planetary Society have said they will issue more details later this year (as reported last month by Alan Boyle). Together with Elon Musk, that means three announcements on manned Mars architectures by major players are anticipated.

The Astronist Mars Strategy

What can we offer here as an alternative?

In the absence of motivated, sustained and visionary political leadership, the route to Mars must take the slow, step by step approach. Mars advocates must get away from the old space agency paradigm of flying a mission, and adopt the paradigm which led to modern global civilisation: that of growing a large-scale, pluralist economy.

Since the settlement of Mars involves tackling several fundamental problems, the only sensible way to proceed is to address each one in turn, and only after progress has been made in each area to proceed towards marrying them together. Trying to do everything at once – Mars One chance to get everything right first time – is a recipe for overreach and failure. We must adopt instead Mars One step at a time.

I’ve written up these points in more detail on a separate page: the Astronist Mars Strategy.

Any feedback, positive or constructively negative, is of course welcome. However, I’m not expecting any thanks from those impatient to see bootprints on Mars dirt.

They will call it a strategy for putting off Mars exploration forever. But I stick to my guns: settling Mars is an immense task, and rushing ahead without laying the necessary foundations will in the long run get us nowhere.

References

Jane Poynter, The Human Experiment: Two Years and Twenty Minutes Inside Biosphere 2 (2006; Basic Books, 2009).

Robert Zubrin with Richard Wagner, The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must (1996; Touchstone, 1997).

Please send in comments by e-mail.

Interesting and relevant comments will be added to this page.

| Site home | Chronological index | About AE |